In the field of physics, an ongoing search is underway for a unified "theory of everything." Obviously, living systems must obey the same physical laws as nonliving systems, laws that can be expressed mathematically. But most investigators consider it unlikely that universal quantitative biophysical laws exist. One reason for this pessimism is that living systems have a mind of their own and strive for advantages under the laws of natural selection. A metal bar, for example, does not need to worry about surviving to have kids. Hence, the theory of evolution is formulated qualitatively. Moreover, different tissues serve different functions and likely are optimized in different ways to carry out these functions.

Despite these arguments, we believe that it is not beyond the realm of possibility that some developmental processes may indeed be governed by biophysical laws. In this regard, we note that the fundamental morphogenetic processes (e.g., convergent- extension and bending of epithelia) and the cellular mechanisms that drive these processes (e.g., cytoskeletal contraction and microtubule polymerization) are relatively small in number and appear to be similar across species.

One of our long-range goals, therefore, is to determine the fundamental biomechanical laws of morphogenesis. As in our other projects, this requires integrating mathematical models and experiments. To date, our models have yielded some promising results, as well as results which are not so promising. Much of our current work has turned to the experimental side of the story, e.g., we perturb loading and examine the effects on morphogenesis, as well as the nucleus and cytoskeleton.

|

|

Compression experiments suggest a universal response of the heart and brain to changes in stress. Like the early embryonic heart tube, the early chick brain tube contracts and stiffens in isolated, unloaded culture causing nuclei to elongate (NST = no surface tension). Compressive loading via surface tension tends to induce opposite effects (MST = moderate surface tension, HST = high surface tension). |

|

|

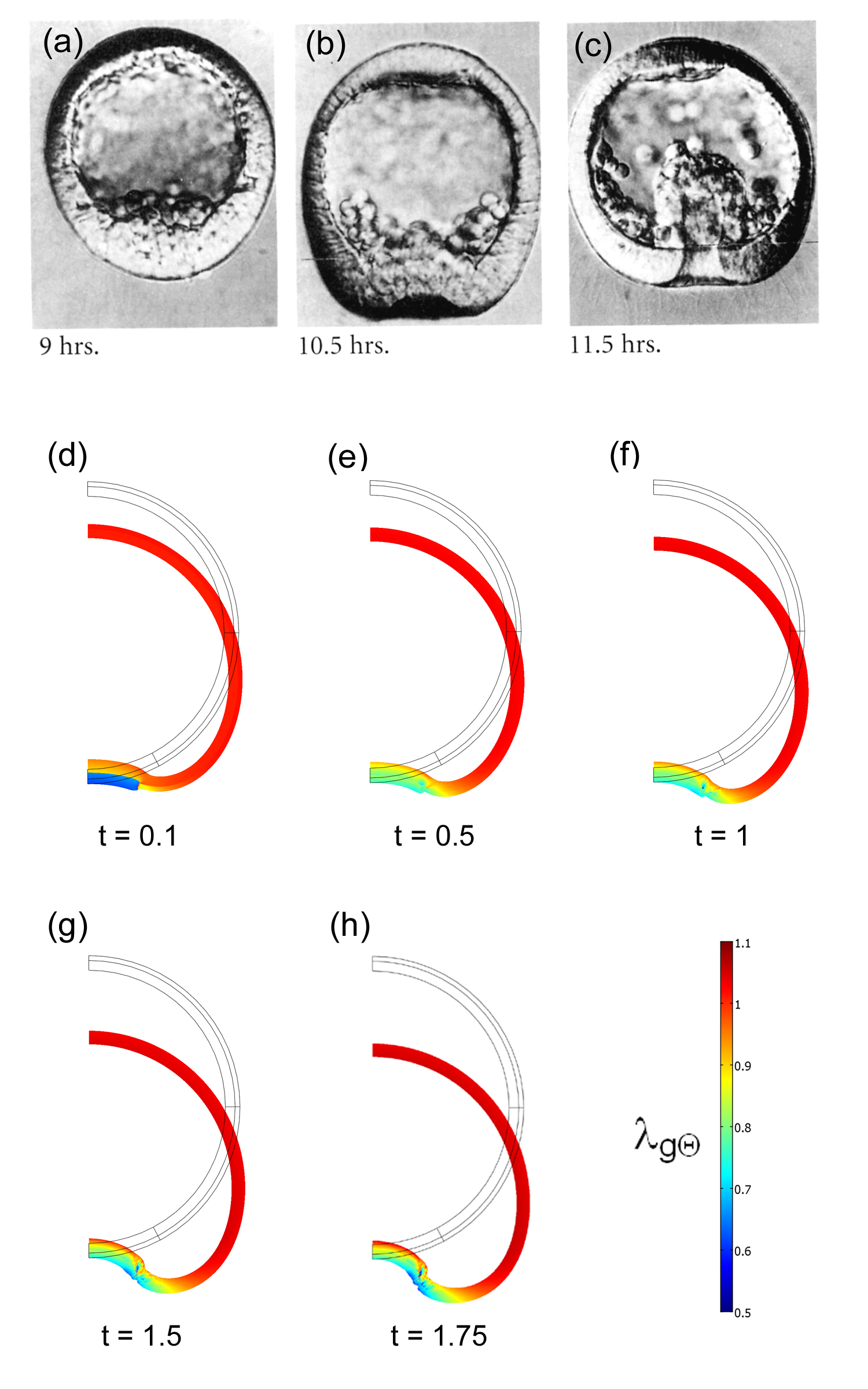

Sea urchin gastrulation. (a)-(c) Sequential cross sections of invaginating embryo (from Gilbert (2003)). (d)-(h) Fluid-filled spherical shell model. Prescribed 50% isotropic contraction in outer region of dimple in (d) triggers hyper-restoration response that continues invagination for t>0.1. Colors indicate circumferential growth stretch ratio. |