Like the heart, the brain begins life as a simple tube. Early in development, local expansions at the cranial end of the neural tube create the primary subdivisions of the brain (forebrain, midbrain, and hindbrain). In many large mammals, the brain eventually folds to allow the surface area of the cortex to grow several times larger than it could without folding. Folding is associated with intelligence, and the human cerebral cortex undergoes substantial folding from the fifth fetal month and continuing into the first post-natal year. Major folding defects are usually associated with severe neurological dysfunction, while more subtle abnormalities in folding have been linked to schizophrenia and epilepsy.

Despite many speculative papers on the mechanisms of brain morphogenesis, particularly cortical folding, the biomechanical factors responsible for normal and abnormal brain development are largely unknown. Extending ideas from our work on heart development, we study the mechanics of brain development during the early phase of primary vesicle formation and the later phase of cortical folding.

|

|

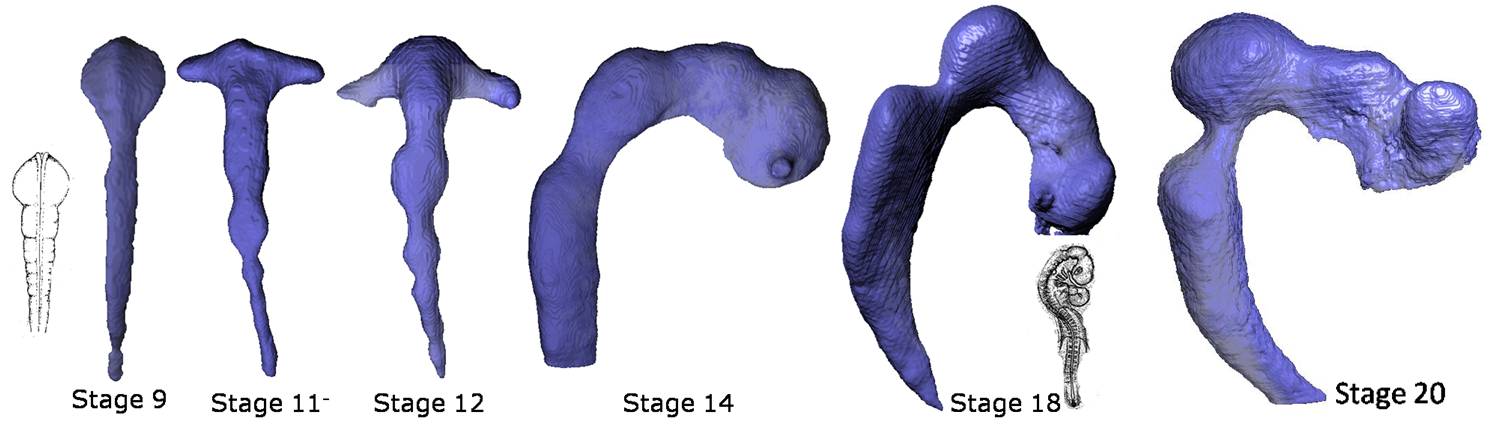

The brain forms as a simple tube but rapidly changes in size and shape as local boundaries are established and pressure increases in the inner lumen of the tube. |

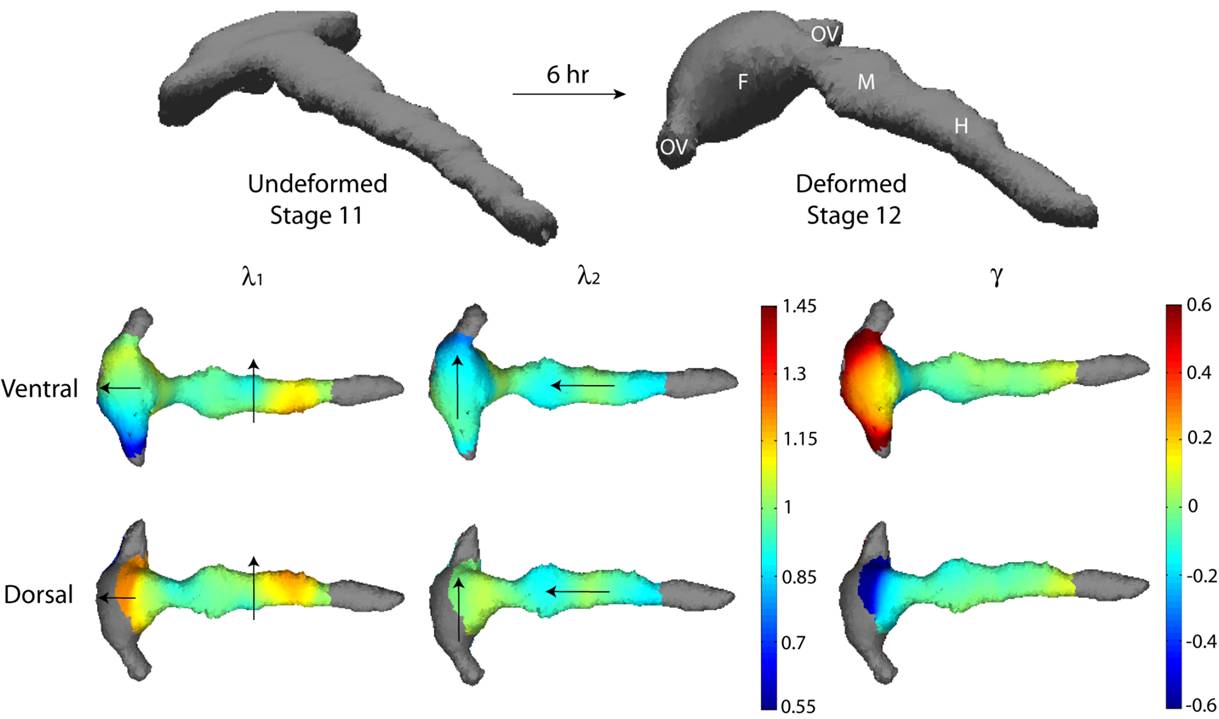

Deformation maps characterize the change in shape of the brain during vesicle formation. Morphogenetic processes such as growth, contraction, and shear can be estimated from such quantities. |

|

|

|

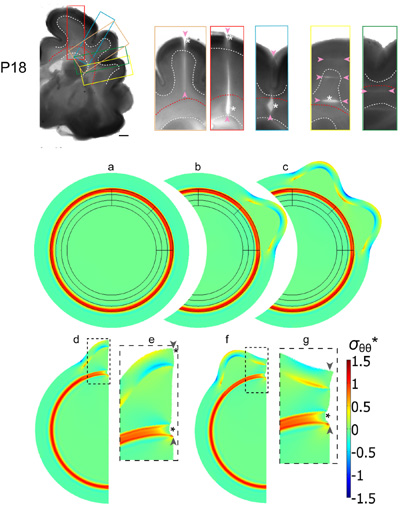

Top: Microdissection assay of developing ferret brain (18 days after birth). Brain slices were cut to probe stress distributions. Color-coded rectangles indicate the regions shown in the close-ups to the right. Cuts of various ranges (indicated by pairs of arrowheads) were made either radially or circumferentially. Significant openings (asterisks) indicate tension normal to cut direction.Middle and bottom: Finite element model for cortical folding caused by phased differential growth. (a-c) Model geometry and stress distribution after each major simulation step, leading to the formation of two gyri in designated regions. (d-g) A section of the model shown in (c) was used to simulate the effects of subsequent radial cuts within a gyrus (d,e) and a sulcus (f,g). The simulated cuts from the cortical surface through the subcortical white matter tract are indicated by pairs of arrowheads, and resulting openings are indicated by asterisks. (Panels e and g are close-ups of the dashed regions in d and f, respectively.) Deformation is consistent with that from cutting experiments above, suggesting that cortical folding is driven by differential growth |