The heart is the first functioning organ in the embryo. In human embryos, the heart begins to beat about three weeks post-conception. During development, the heart undergoes a remarkable transformation from a single muscle-wrapped tube without valves into a complex four-chambered pump, while simultaneously providing continuous circulatory support to the rapidly growing embryo. Since form and function are intimately interrelated, these changes must be carefully coordinated.

Our work in this area deals primarily with the formation of the early heart tube and the subsequent process of cardiac looping, as the initially straight heart tube bends and twists into a curved tube that normally is directed toward the right side of the embryo. Looping is a crucial process during heart development. Looping abnormalities cause many of the cardiac malformations that occur in as many as 1% of liveborn and 10% of stillborn human births. Moreover, such defects may result in numerous spontaneous abortions during the first trimester. To fully understand the origins of congenital heart disease, it is important to determine the biomechanical factors that drive and regulate looping.

Because development of the chick heart parallels that of the human heart, our experimental model is the chick embryo. (Contractions begin at about 30 hr of incubation in the chick.) Our computational models are based on the equations of nonlinear continuum mechanics, modified to include morphogenetic effects (e.g., growth and contraction). This strategy has allowed us to identify forces that drive and regulate looping, findings that had eluded researchers for nearly a century. More recently, we have developed and tested a hypothesis for the formation of the head fold, which is a structure that initiates development of the heart, as well as the brain and foregut.

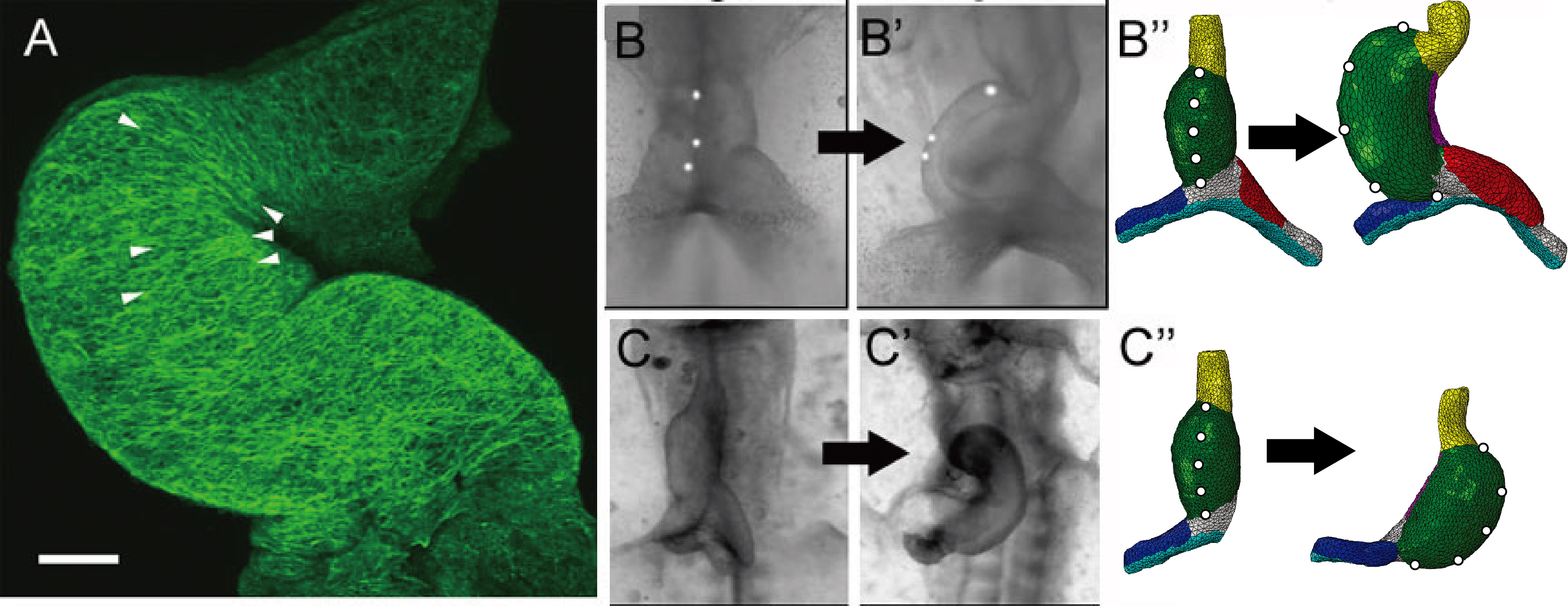

Illustrative examples from our work on heart development. (A) Actin cytoskeleton of stage 12 chick heart (two days of development). Note the circumferentially aligned fibers on the inner curvature compared to the randomly aligned fibers of the outer curvature. (B-B'') First phase of looping; the initially straight heart tube (B) heart bends and twists into a c-shaped tube (B'). Our finite element model yields similar changes in morphology (B''). (C-C'') Development of heart with primitive left atrium removed; heart loops abnormally to the left (C,C'). The same model as in (B''), but with left atrium removed, yields leftward looping as in the experiment (C'').

|

Cardiac c-looping in chick embryo. (A–C) SEM images of embryonic chick hearts during c-looping (ventral view). The originally straight heart tube (HT) at stage 10 bends ventrally and rotates rightward, transforming into a c-shaped tube at stage 12. Note that artificial labels along the ventral midline of the HT at stage 10 move to the outer curvature of the looped heart. (A'–C') Rotation of the HT is indicated by the orientation of the lumen (red dashed lines) in OCT cross sections (yellow dashed lines in (A)–(C)). CJ = cardiac jelly, DM = dorsal mesocardium, EN = endocardium, MY = myocardium, SPL = splanchnopleure, OV = omphalomesenteric vein. Scale bars: 200 µm. |

|

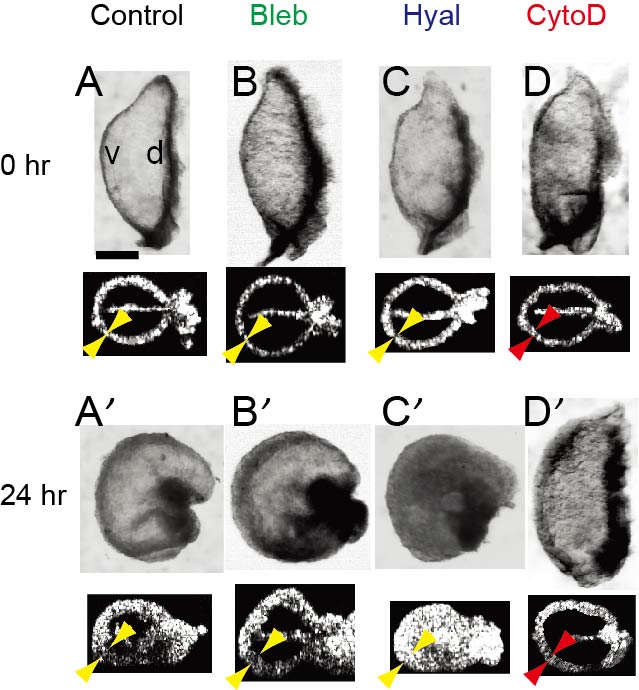

Laboratory experiments of ex ovo culture are important to eclucidate the mechanisms that drive bending of the c-looping heart. Embryonic chick hearts were isolated at stage 10 (0 hr) and cultured for 24 hr in various conditions: control, 30 µM blebbistatin (Bleb, contraction inhibitor), 20 UTR/mL hyaluronidase (Hyal, enzyme for dissolving cardiac jelly), and 100 nM cytochalasin D (CytoD, actin polymeriztion inhibitor). Bending occurred in all cases except the hearts exposed to CytoD, which inhibits hypertrophic growth of myocardial cells. Inhibition of myocardial growth was also confirmed by the reduced thickening of the myocardial wall in CytoD-treated hearts (red arrowheads). These results in conjunction with measurements of myocardial strain and stress suggest that bending of the heart is driven primarily by differential hypertrophic growth in the myocardium. Scale bar: 200 µm. |

|

|

The biophysical mechanism that twists the heart tube during c-looping was explored through (A–D) experimental mechanical perturbations and (A'–D') computational modeling. (A) Straight heart tube (HT) at stage 10-. (B) Same heart at stage 12 after 6 hr of culture. (C) Most rotation disappeared as heart untwisted after removal of the splanchnopleure (SPL), but the HT remained bent slightly toward the right. (D) The HT tilted toward the right after transverse dissection of conotruncus (black arrow) and longitudinal dissection of dorsal mesocardium (DM, brace in (C)). The ressemblance between the experimental results Buy Alprazolam and computer simulations is striking. These results support the view that twisting of the HT is primarily caused by compressive loads exerted by the SPL, with looping direction determined by unblanced lateral forces supplied by differential growth in the omphalomesenteric veins. Scale bar: 200 µm. |